It’s funny how money changes situations

Lauryn Hill, “Lost Ones”

Within the literary community there are lots of thankless jobs—the volunteer readers, the unpaid editors, the DIY chapbook makers—all enrich the landscape that allows for emerging writers to get their start, and for established writers to continue finding readers. But literary journals and small independent literary organizations all need funding of some sort. I was curious about the germination and maturation process of a literary journal, and curious about the ethical questions that are faced. I was honored to talk with David Housley and Dan Brady from Barrelhouse, a literary magazine that also hosts two literary conferences a year, called Conversations and Connections. With nearly 20 years of publishing behind them, many of the tough questions that arise for editors and publishers have been asked of and by David and Dan. Through it all they’ve found ways—like in the best Dungeons and Dragons campaigns—to flexibly operate within their own ethical rules. What follows should help anyone thinking about starting a literary journal and concerned about how to pay for it.

What follows is a practicum (the tough questions I took away from the interview) and our conversation on how to fund literary journals and independent literary organizations.

The Practicum

How are you imagining stability? Are you imagining continuous growth? Are those in conflict?

Are you willing to change your funding model in response to what isn’t working? How are you set up to pivot when needed?

What ways can you diversify what the lit journal offers beyond a print magazine or online publication?

How do you negotiate your ethics within a group structure?

Steven Leyva: Alright, well, thank you for being a part of Tough Questions for Mason Jar. One of the things that I wanted to talk to you all about was finance, and about how you make the sausage of a literary journal and literary organization. I want to talk a little bit about the ethics of that. I want to talk about the pitfalls you've tried to avoid. But maybe you could just start with how you initially brought Barrelhouse into being. What's the superhero origin story of Barrelhouse?

David Housley: Well, I can do that. Dan came along about a year later. The origin story is, a bunch of us were in a writing group together—we were in a writing workshop—and when it ended we kind of looked at each other. We were like, we could keep this going. So we kind of rolled out of that into a writing group. We met in bars and eventually we found we were spending as much time just kind of bullshitting as we were doing the writing workshop part, and then—like any group of writers that gets together and starts drinking—we started complaining about literary magazines and outlets, and how there weren't the kinds of places that we were looking for at that period of time. And we just happened to have a group around the table that, well, I do web stuff still for a living, and one of us was an editor, one of us was doing grant writing at the time, which turned out to not actually be anything we ever did. But it just seemed like, oh, we actually have people around the table [who] might be able to actually try to make that happen. So we started talking about doing our own literary magazine. And I think I know I've heard Mike Ingram tell the story before, where he says they all kind of forgot about it. And then the next week, when we came back to the writing group, I had all these literary magazines with me and a spreadsheet of how print on demand would work, and how we could actually do this, and get started for not a lot of money. Because print on demand was there, and I do enough to kind of spin up a website on my own. I knew graphic design people, and I just kind of came in with this to say that I created Barrelhouse, but I did kind of come in with a spreadsheet and a bunch of other literary magazines, and say, hey, you know this is actually something. I think we can do it.

SL: You were already thinking about how to overcome the barrier. That first barrier of how we're going to pay for it like before anything got made. You're like, “I'm gonna circumvent that and say there's a way we can do it. It's possible.”

DH: Yeah, I mean, I knew that was going to be, obviously, the big question. And I knew a little bit about print on demand, just from working in the communications offices in my professional life. I knew that was going to be a question we'd have to figure out.

SL: And, Dan, how did you come to be involved a year later?

Dan Brady: I was in grad school at George Mason, here in Virginia, and I was at a bookstore in DC. I think it was Kramer's in Dupont Circle, and I saw a copy of Barrelhouse on the shelf. I picked it up and read it, and I was like, This is amazing, and it's made here in DC. Like I should get some of these people and see if they need any help. So I did. I emailed and Dave and the other folks were like, “Sure, meet us for a drink, let’s talk.”

SL: I see that drinking is always sort of connected.

DH: We sent him home to his now-wife after several drinks. It was maybe not the best, or maybe it was a good introduction for her to what it was going to be like. If, when you were a part of Barrelhouse, it’s sort of a fraternity of lushes. Right?

SL: Well, Dan, what's the first thing that you did coming in? What was the job you had?

DB: I was in grad school for nonprofit arts management. So, I, you know, looked at Dave's crappy spreadsheet—

DH: We knew by then that we needed someone like [Dan] to just show up. And it was really great.

DB: Yeah, it was like, you know, we should look at incorporating as a nonprofit. We should look at how we're going to do marketing and fulfillment and distribution, and all those non-editorial things that you need to do to really have the magazine run. I think my first title was like Business Manager or something like that. But I'm a poet, too. So within a year or two I was also the poetry editor.

But we did that. We went through the Maryland Volunteer Lawyers for the Arts and they helped us get our nonprofit status. And we got a modest amount of donations. In the beginning all the editors were just paying for the printing themselves, and we weren’t breaking even; that took probably five years to happen. We did get a grant at one point that paid for like two issues to be printed, and that really gave us enough runway to do the things we want to do and not worry so much. And by the time that money had run out, the magazine was kind of paying for itself with sales.

SL: That's interesting. That was going to be my next question. What were the things you did incrementally to move from taking a loss on the printing to being revenue neutral to whatever it progressed to beyond that?

DB: It's hard to remember the order of things. So, let's see. I think the conference, the Conversations and Connections Conference in DC started first, and that was, and still is, a huge revenue stream for us. Probably like about a third of our revenue comes from that, I'd say. So, that was a huge, huge help. We continued to get sort of modest donations. We got distribution for the magazine, which is kind of a double-edged sword, because they order a lot up front and you don't know if it's gonna sell. But, pretty quickly we were even on the distribution front, and we considered that as marketing because people would find [the magazine] at Barnes and Noble, and people would write to us from Utah and be like, “Hey, you guys have a great magazine.” We're like “holy crap, people in Utah are reading this magazine!”

SL: And they found it the same way you found it!

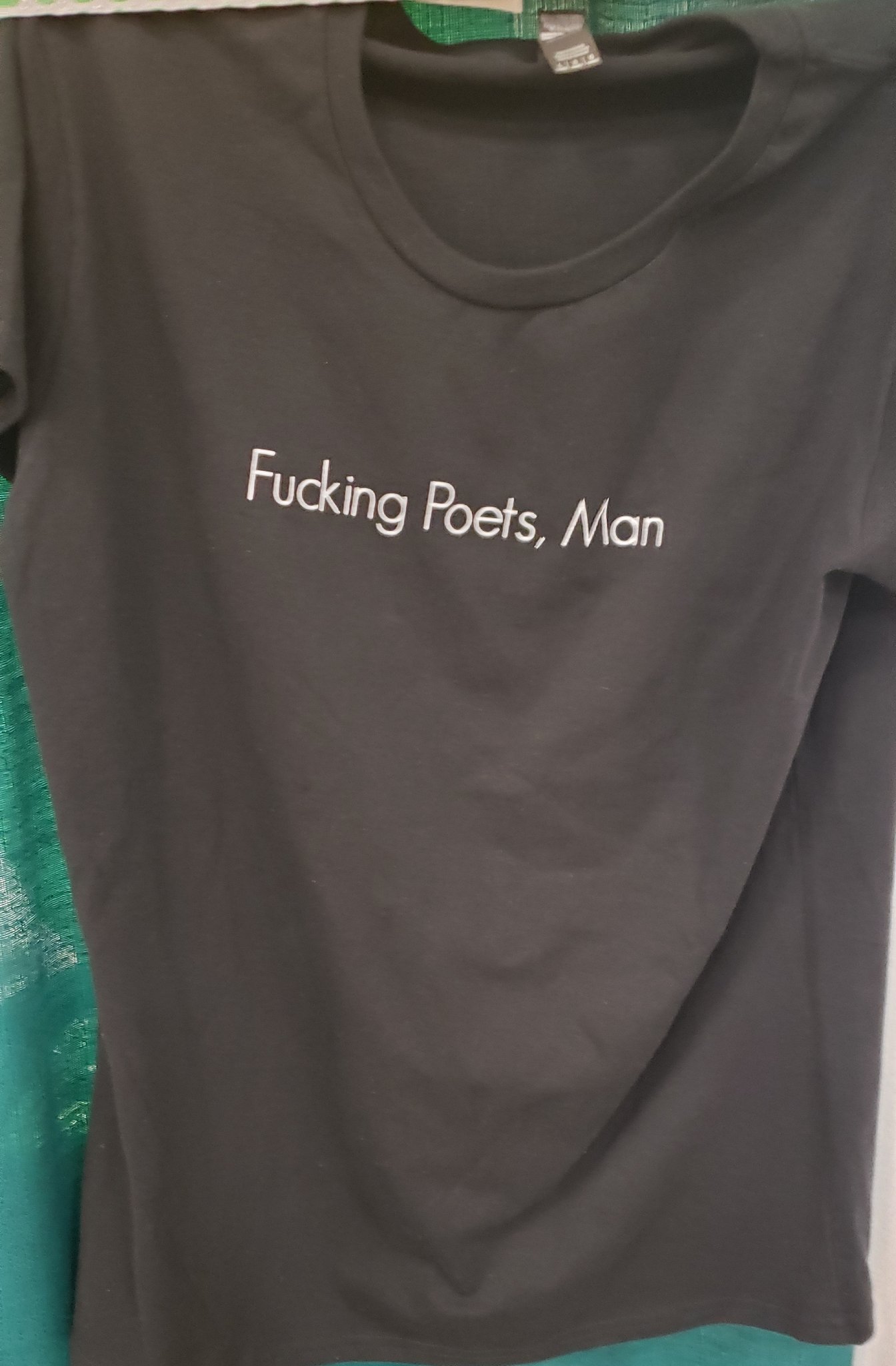

DB: Yeah, I mean from there we added the Pittsburgh Conference, which is more money, and we joke that we're a T-shirt manufacturer that also sells magazines.

SL: I've seen the poet shirts before.

“Fucking Poets, Man” t-shirt from Barrelhouse.

DH: We hit a nerve with that one.

DB: Yeah. So we just started kind of diversifying. And we've done online workshops which make a decent amount for us, and then writer camp. We keep everything really cheap for the users or the readers, but we always have like a little bit of profit coming in from that. Which helps us keep going.

SL: So at one point the conferences, the T-shirts, the other things were subsidizing the printing. But now has the printing, or the sales of the books and the distribution, has it really allowed it to pay for itself, or are you still subsidizing printing from those other revenue streams?

DB: For the magazine it essentially breaks even on its own, through sales and subscriptions. And we've since expanded into books, and they're more of our loss leader now that the other are supporting. But we're getting better at those too. I think we know we'll get there.

SL: And how long has Barrelhouse been going?

DB: Great question. 2005 we started, I think. Is that right, Dave? Or 2004?

DH: That sounds right to me. I was trying to figure out how many conferences we had done, and I think the one we're doing in Pittsburgh in a couple of weeks is going to be the twenty-third. It's been a while.

SL: So, you're a magazine that could legally drink, right? I wanted to know a little bit about the ethical concerns. What are some ethical concerns or conversations about ethics you had around how to make sure that, to use an idiom, no one fucked up the bag? How did you make sure there were ways in which you might have been transparent, but also that things would be able to continue in a way that didn't require, for lack of a better word, the cult of personality?

DH: Good question. I’ll wait for Dan to answer.

DB: Among our group, we're pretty transparent about finances, like I post things to our Slack all the time—money-situation wise—and we meet in person at least once a year to go over that and say, like, all right, we're spending too much on this, and you know we should be spending more over here. We, I feel like, are pretty transparent publicly with that, too.

A couple of years ago we would do this infographic that showed you pay 75 dollars to come [to the conference], but 20 dollars of that goes to other participating magazines, this amount goes to the speakers, this amount goes to Barrelhouse. So we kind of publicly broke that down. We internally have a lot of discussions about money that's out there that we could go for. But we choose not to like the Amazon literary partnerships and other things that we're just like, “Yeah, it's not really our thing.” We would feel kind of bad putting into that. So, there have been talks like that, too. I think just keeping it open amongst us, and people can ask questions and like how much we’re paying for this and why are we doing that? It's a group decision making body.

SL: So what I was going to ask is, who has the final say about how money is spent? Do you vote? Do you have to be in unanimous agreement? How does that work for you all?

DH: We're a loose collective. So, there are I think ten of us who are editors who just kind of form what in a different organization would we be a Board of Directors, where we make decisions about future things we're doing. If there's what we might consider a difficult decision to be made, we'll make that. We make decisions about what we spend money on, although we don't spend a lot of money; that's the other thing. None of us get paid, so we get paid in a couple of Airbnbs and a couple of dinners a year. Basically, most of the things we’re spending money on are either printing new books, or printing the magazine, or the really low costs associated with running the conference.

One thing I think we've been really smart about is not to put ourselves in a position where if something doesn't work, we won't exist anymore. So, we won't put ourselves in a position where we have to spend ten thousand dollars to get a keynote speaker to make twelve or fifteen, because if we do that and we make eight, then maybe we don't exist anymore. And there were times when we used to have keynote speakers at the conference, which is what I'm referring to, and I would be literally like waking up in the middle of the night thinking, Oh, my God! Like is this it? Am I going to run us into the ground because I can't get enough people to this conference to pay the person who's going to come be the keynote? And then we're going to owe two thousand dollars we don't have, and we won't exist anymore. So we don't have a keynote anymore. We found a model around the conference. Honestly an Airbnb for two nights is by far our largest expense for running the conference.

When we do our writer camp, the model that we arrived at with the host of camp basically allowed us to start risk-free, where it was just a complete shared profit model and we didn't have to lay out X amount of money. I think we're very fiscally conservative. I hate to even use that word, but we are. We were scared straight. We were scared straight those nights all those years when we weren't sure if we were going to ever have enough money to print another issue, and those nights when I would wake up in the middle of the night and think, Oh, my God, I got to sell 50 more tickets to this thing, or we might not exist anymore. So we've been through that, we're very careful about not putting ourselves in that position anymore. And I think that's one thing that's allowed us to, like Dan said, talk through an opportunity and say we could go for this, and put X amount of dollars toward that, and probably it's going to pay off, but we've been reluctant to do that because while we came through those years just fine, ,—I feel like I was scared straight especially— we came through it really not wanting to take those kinds of risks. Especially now that we're kind of a larger, loose collective and it kind of accompanies more, and I'd hate to do something to burn it to the ground because we took a risk we didn't have to.

SL: I think I attended one of the conferences in Pittsburgh myself. At Chatham I saw Hanif Abdurraqib. Which was lovely. But I get it. I gotta ask, what's the highest you all paid for a feature speaker?

DH: When Hanif was there we were not paying. We were in our current model, and we caught Hanif on the way up. So, we were really lucky. There's some folks we caught like him that I'd say we caught on the way up. The current model is we have featured speakers, and with your registration for the conference you choose one of those [featured] books, so we pay fourteen dollars per book to either the publisher or the author. The author kind of decides whether they want to buy their copies and get paid directly. We've talked about if we should pay travel fees for those folks. And that's something we're still kind of noodling through. But, I mean, if you said, “Hey, you're going to sell between 25 and 40 books on this one day,” it's a pretty good opportunity.

SL: I was just curious, because I didn't realize you were having sleepless nights about how to pay speakers!

DH: That was before we found this model right now. There was like a sweet spot where they were on the way up, but they didn't have a speaking agent yet. That was the kind of person we would look for, and that was usually, I think 2,500 dollars is what we would pay, and that's when I would wake up in the middle of the night and think, Oh, man, if we make 1,500 for this conference, and I have to pay 2,500 plus travel expenses, we don't exist anymore.

DB: We were very worried about the reputational risk of not being able to pay those folks, or to do something for a while, and then not be able to do it, because our finances changed. We wanted to pay contributors to the magazine, and we kind of held back because we were like, well, we don't want to pay people for issue fourteen, and then get to issue fifteen, and be like, sorry, we don't have the money to pay our contributors. So, we waited until we knew we had enough cash flow, and things were going to be fairly regular so we could say, all right, for every issue this is our budget to pay contributors. And to Dave's point, paying for travel and stuff like that,hat stuff we look at regularly like, what's the next thing we can pay for?” We feel like we should pay for it if we can. But it's just the question of is it going to be fair to everyone? Can we say from now on we're paying for this?

DH: Web contributors, for the longest time, we weren’t paying, and I think we were fairly scientific about that. We did a special workshop to make a certain amount of money to pay for web contributors for a year. Just so we could say, let's see how this goes. And then, since then we've been paying web contributors.

SL: It's such an important conversation. Full disclosure, in your 90s issue you published a poem of mine. Which I was really grateful for, early in my career. And I’ve thought a lot about the way in which the publication is providing a way to share work via web content, with social media and stuff like that., but the writer is also generating content for the website which then, depending on the publisher’s model, might be driving ad revenue, et cetera, et cetera. So, you, as a publisher, definitely have written content for free. But we don't usually talk about it in those terms, right? So it's interesting to hear you all talk about how you sort of work towards how to do right by people.

Were there any times in which you had some missteps where someone said, “Hey, I don't know if this seems quite right,” whether internally or externally?

DB: We had one editor who was in charge of a print issue just by themselves, and this was soon after we started paying contributors, and he accepted like, I don’t know forty pieces.

DH: It was the most expensive issue we're ever going to put out.

SL: I hope it was fire! I hope it was good.

You might know that I was editor for the Little Patuxent Review for about five years, and one of the things at the time I really appreciated was that I just had to be an editor, I didn't have to think about finances at all. The Board of Directors essentially made sure that things got printed. Do you ever find it difficult to do those dual roles, to both be thinking about how something editorially is coming together, and having to think about how to pay for it?

DB: Yeah, it is. For example, I was thinking about this earlier, right before Covid hit, we had our best year ever, and our revenue now is about a third of what it was in that year. So we were on this huge upswing, and then the conferences went away, and we weren't publishing as many books or magazines, like everything was kind of on pause.

DH: We took a year off from Writer Camp.

DB: So, we're looking at our budget, we're like, “Can we keep doing all the things that we were doing and want to do?” And we're still kinda trying to get back to where we were. It's a question every time, like, can we really publish this book? Can we really do this thing that we want to do? And is it going to be as successful as before? So yeah, I definitely feel that tension of if the money is there or not.

SL: What's the next thing in terms of scale for you all? Are you in a sweet spot in terms of your finances in which you've hit a groove? Or is the goal to be in a position to invite other kinds of financial partners to scale the operation?

DB: I think we're pretty comfortable where we're at. We want to pay everybody more. We don't want to get too big. We don't want to partner with the University, because I feel like the magazines we've seen do that go away. Their market gets cut, and then the magazine goes away. So we like our independent position. I don't know, I mean a lot of things like Writer Camp were just a dumb idea. And we were like, all right. Maybe we should try this. So who knows what the next nice dumb idea will be?

DH: Yeah, I think we're a safe space for ideas. When we started, something went really wrong at the conference every year for about eight years, and then one year it didn't. We were like, “Oh, wait! We’re at the end. Nothing terrible happened today!” So, in writer camp, we just kind of made it up on the spot. I don't know if any of us had ever been to a retreat or residency before that, we just decided to have one. So yeah, I think we're a safe space for new ideas. And so we're pretty careful about not putting ourselves in risky positions which could limit some of those new ideas. It really limits scaling in general. But yeah, I don't know what's coming down the pike. I think there are some interesting book and book series ideas that are kicking around. So yeah, we'll see. But I agree, we’ll kind of stay around our same size and feel comfortable, and we're in a position where we generally don't have to worry as much about whether we're going to exist the next year. That, to me, that's just the baseline goal. I'd like to also exist in 2023, 2024. Aside from growth, that would make me happy, so long as we're able to still do the things we do, and still be that safe space for ideas, I think we're pretty good.

SL: It sounds like equilibrium is a value versus continuous growth. Which I think a lot of people can appreciate. Were there any other magazines you looked at when you all were beginning in terms of financial models? How did you do it beyond trial and error? Were there any things that you took from others to make it easier for yourself?

DH: I don't think so. Dan, I know until you got there, we weren't even really smart enough to talk to anybody else about money. We were just kind of trying to keep our heads above water and kind of stay alive, and we connected pretty early with Aaron Burch from Hobart and Matt Seagull from Pank, and Roxane Gay from Pank, Richard Peabody from Gargoyle, who's a local, obviously like lit-mag-legend who is one of my teachers as well. But I don't know that we took anything from them in terms of how to run things. We started talking to folks like Aaron and Matt and Roxane about, you know, “Where are you printing? How much does it cost you?” And there were some other folks involved in those discussions. So, we did eventually start trying to connect with some other people and try to say, “Hey, we're kind of all in this together, we should be sharing information about how we can all stay alive.” But in very early days I think we were too stupid to even have those conversations with anybody.

DB: We never, I don't think, sought to be like a really big, prestigious, important magazine. We want it to be a fun, cool magazine, and I think we did that by keeping our group of editors tightknit and open to each other's ideas, and not stressing too much about how we need to be the new Tin House, or whatever.

DH: So yeah, I think we really hit a place where our lane was kind of being the friendly welcoming space. Hopefully, you felt that at the conference.. And Dan, I feel like you should talk a little bit about distribution, because there were a couple times in our history with distributors, where they put in requests that were going to scale us up to a place where, if that didn't work out, maybe we didn't exist the next year. And I don't think any of us actually knew that we could push back on that. So you kind of stepped in.

DB: Yeah, I mean, there was a while there where the distributors started doubling their orders. And like I said, you know we have to pay for the printing upfront, so that was a huge increase in our printing costs. I reached out to them, and I was trying to understand this big change and it didn't really seem like there was that much demand, or like suddenly every Barnes and Noble wanted us. They didn’t really have a good reason. And then things sort of started to pay back a bit, and there was a time they wanted us to make the magazine available in Canada, which again would have increased our upfront cost quite a bit, and we just kind of talked about it. We're like “I don't know. I think if it could go poorly, we're sunk, so let's just not do that.”

SL: What was the reasoning given, if any, for why there was an increase in the order from the distributor?

DB: I think it was like, they could look at like how magazines were doing overall. So in their business head we were in that group with Tin House and Ploughshares and stuff, and I guess those other magazines have seen kind of an increase in sales. And so they thought maybe they could place a bet on us and have that pay off.

DH: But we were placing that same bet. So yeah, also, if that bet failed, we were the ones that were going to lose, which is a great position to be in if you're not us.

DB: Yeah. So, I mean, the distributor buys the copies for 50. Basically, we need to sell half of the copies we send them in order to break even on the distribution deal from a printing cost perspective. And if all of a sudden they're ordering 500 more copies, and then those copies don't sell,we don't make that 50 percent and we are losing a lot of money.

SL: Is the agreement with your distributors that those copies are returned? I know there's a way in which sometimes they're destroyed. What was the situation?

DB: Yeah, the copies that aren’t sold are just destroyed. So we wouldn’t be able to get them back to sell on our own site or anything.

SL: Yeah, Sounds like a sucker’s bet!

DH: At first it sounded like amazing, great news. You know, like, “Oh, wow! The distributors are betting on us growing!” And then it sounded like possibly a sucker's bet.

DB: I don't remember what it was, some small press had a book that all of a sudden became like a huge hit, and the distributor ordered thousands of copies, and the small press printed them because they wanted to get the book out. But then those copies didn't sell, and that press went out of business immediately after their biggest hit. We were friends with those people when it happened. And we don't want to be in that position. We don't want to ruin everything by getting too successful too fast.

SL: Yeah, it sounds like there weren't models that you were looking at about how to structure yourself around. But there were a lot of cautionary tales that you were encountering, and like what you said, “I don't want to be like that.”

DH: All the time.

SL: For folks who want to be in a DIY spirit, who want to start new journals, what financial advice would you give to them?

DH: I would say that we learned that idea of being scared straight, that we don't want to put ourselves in the position where we might not exist if it doesn't pay off. So the idea of being pretty careful, I think that's something.

DB: Yeah, I think also, when people are starting out, they're usually just starting out themselves or with their friends, and you don't want to put yourself at bad personal financial risk, like we were paying in to print the magazine, but it wasn't like a crazy amount of money. But I think that some people get in the position where they're trying to do too much on their own. And then the credit card bills pile up, and then you can't pay your authors and like that’s when you get called out on social media and that’s the end of your press and your literary life.

SL: So for sure, nothing will get you called out as much as saying you're going to pay an author and then not being able to.

DB: I think just being cautious and knowing what your limits are when you start out and growing slow, like you said. We've been around for 20 years or something, and it's taken a long time to build the magazine and the organization that we have. We started out as just a bunch of people at a bar trying to sell like three copies of this magazine.

SL: I ask that question because I think anyone starting out is not aware of what their limits are. They don't know what questions to ask. They don't know necessarily where they might be entering into a kind of risk. All they know is that they want to try. And I’ve been thinking very deeply about the way in which it matters how we make things easier for the folks that come behind us. I think it's wise to be cautious. It's wise to know your limit, but also give yourself space to think about discovering what those limits are, because they're not necessarily the same for each person.

DB: We don't do it post Covid, but we used to have a program called Amplifier Grant, where we would give, I think it was 1,500 dollars to a magazine or literary nonprofit that was starting out, trying to do something new, trying to grow. We did that every year for several years. We feel like we benefited so much from people like Richard Peabody, and Red Levixon was a really great man in time who told us so much in those first couple of years. So any opportunity we have to bring new magazines to the conference or have somebody come to Writer Camp and talk about what they do, you know, we want to create that platform as much as we can. So yeah, I think that the advice would be to plug in to the people who you think are doing a good job. Learn from them. They'll tell you all the bad things that they encountered along the way.

SL: To ask some tough questions, right?

DH: All this other stuff that's grown up around the magazine has been really cool, and it's obviously helped fund the core thing. So I always tell people to look for other opportunities. You can become a part of the community. You can start to grow your community. If you just want to put out a magazine or run a website, that's cool. But you also may have an opportunity to start doing some other things, and I think we see a lot of groups that we work with in DC, Baltimore, that are growing in that same way. What you're doing right now is part of Mason Jar growing and starting to do new and different things, too. So, I think there is that opportunity, and you don't have to have everything figured out to start trying to get into some other things. I think there are lots of opportunities there, and we can maybe just serve as a grab bag of ideas for the types of things you might be able to do that might help fund that central thing.